When the Great Depression hit the United States in December of 1930, everyone suffered. The national income dropped by 50 percent and the unemployment rate skyrocketed.

African Americans, though, were hit harder than most.

According to the Amistad Digital Resource for Teaching African American History, “white unemployment had hit an extraordinarily high rate of 31.7 percent in 1931, [but] it was well over 50 percent for Black Americans.”

It was during this time that Father Divine’s Peace Mission Movement rose to prominence, in no small part because of his policies of inclusion and his early work toward civil rights.

Jobs in agriculture had become almost nonexistent for African Americans. Cotton prices had dropped from 18 cents per pound on the eve of the Great Depression to less than 6 cents per pound by 1933. Many black sharecroppers in the South lost their farms to whites, and the government did little or nothing to intervene.

Those who moved North, seeking industrial work, fared little better. African Americans were hired last and fired first — and wage discrimination meant even those who could find jobs were still in poverty. Black women were paid even less than the men — conditions were so bad it became known as the Depression-era slave market.

In the South, things grew especially violent. On the railroads, unionized white workers and railroad brotherhoods attacked and murdered black firemen in order to take their jobs.

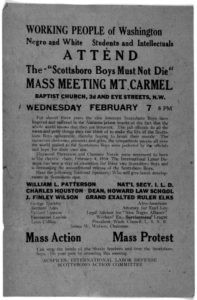

The Scottsboro Trial

This flyer called for a meeting to protest the “Scottsboro Boys'” conviction. Source: Library of Congress’ Rare Books and Special Collections Division, Washington, D.C.

Amistad reports that in one infamous Depression-era incident, known as The Scottsboro Trial, “A group of young black men had heard of government jobs being offered in Memphis and were on their way to investigate. They would never reach their destination. On 25 March 1931 nine young African Americans were arrested in Alabama on false charges of rape. The young men had hopped a ride on a freight train traveling between Chattanooga and Memphis, looking for a free ride on an unusually warm spring afternoon. After getting into a fight with a group of white youth, the black men were violently hauled of the train, arrested, and charged with the rape of two young white women said to be aboard the train. Despite the lack of evidence, within a few days all nine men had been indicted. Blacks were excluded from the hastily formed all-white jury, and the defense attorneys were given only twenty-five minutes to consult with their clients before the trial began. All nine African-Americans were found guilty and eight were sentenced to death in the electric chair. Leroy Wright, who was only twelve years old at the time, was spared the death sentence.”

Meanwhile, soup kitchens, charity groups and even public assistance programs engaged in blatant discrimination: Public assistance programs provided blacks with less aid than whites, and some soup kitchens excluded blacks altogether.

Peace Mission provided Great Depression relief

As conditions worsened and hopes grew dim, Father Divine’s International Peace Mission brought critical relief to tens of thousands. Divine himself became more political, calling for, among other things, an end to segregation in schools and equal rights for all.

In 1932, he moved the mission’s headquarters from Sayville, Long Island, to Harlem, and expanded efforts to provide food, employment, and shelter. There he created a network of hotels, restaurants, gas stations, grocery stores and clothing shops — at one point, the Peace Mission was the largest property owner in Harlem.

And unlike the other organizations, Divine’s Peace Mission helped anyone, regardless of race.

“Because your god would not feed the people, I came and I am feeding them. Because your god kept such as you segregated and discriminated, I came and I am unifying all nations together. That is why I came, because I did not believe in your god.” — Father Divine

Recent Comments